Soledad Salamé: FORCED by NATURE

Sep 17, 2021 to March 27, 2022

The Transart Foundation for Art and Anthropology

1412 W Alabama St, Houston, TX 77006

This exhibit will be available for a private viewing by appointment only, from March 24 to March 27, 2022.

Mask required. Please contact Surpik Angelini at Surpik@mac.com

Artist’s Statement

My art is a conceptual and visual exploration of the intersection of science, technology, and issues dealing with social justice defining our present time. Engaged with the political implications of our environmental crisis, my recent work maps vulnerable marginalized communities suffering the greatest consequences of natural disasters.

Working in glass, silk, and paper effectively extended my visual vocabulary, incorporating textual relief elements to underscore our collective negligence regarding climate change, including the rapid melting of glaciers and polar ice caps. Climate change has triggered people’s migration from areas affected by rising water and unstable weather. In the USA, Border security policies intensify the social impact of migration, exacerbating unsustainable environmental practices.

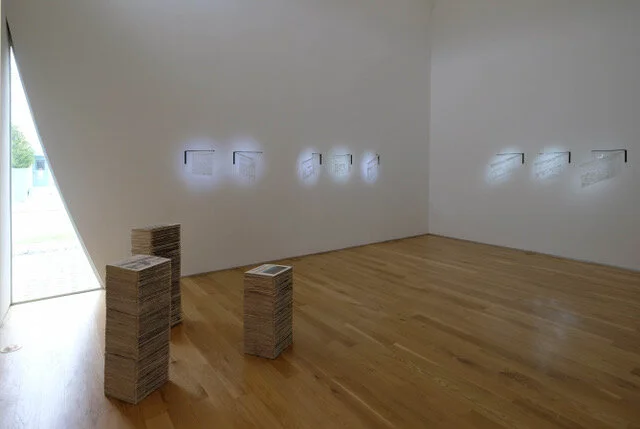

Our world is in constant flux and transformation. The way we communicate our actions’ consequences has been transformed. We once created a tactile object- a newspaper -- providing a richly physical interaction made from plant-based paper; today, with the slow death of print media, we interact with world news through digital reporting, easily distorted or manipulated. Among my most recent explorations: Newspaper, Almost Transparent mimics folded newspapers. On the surface, the engraved images of selected articles capture light and cast still shadow images, preserving the historic instant in an ephemeral shadow on a wall.

I wish to record changes in our environment as a call to action to protect both the earth’s precious natural resources and its people, while pointing to the fragile beauty surrounding us. By magnifying the pleasures inherent in natural materials -- paper, textiles, and even sand-based glass – my work seeks to remind us of the magnificence and splendor that may be lost if we do not protect the environment.

Soledad Salamé: Moving Through the Earth, Crossing Borders and Boundaries

by Edward J. Sullivan

For many years, I have lived with a large-scale print by Soledad Salamé. It is a graphite and acrylic piece from 2006 and belongs to the series called Antarctic Reflections (Fig. 1). These works were first seen publicly in an exhibition called “Aguas Vivas” at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Santiago, capital of Salamé’s native Chile. The tones in the print are pale blues, greys and varying shades of white. “Aguas Vivas” means “Living Waters” and it is important to understand not only the meaning of this term but also, its connotations for the overall concept that the artist deals with in this, and subsequent projects. The waters of the Antarctic, indeed all waters, are alive! They contain the kernels of existence. Not only do they shelter incalculable numbers of organisms, they also provide the sustenance for the flow of life throughout the planet. Water in Soledad Salamé’s art is the essence of existence, but it is also a harbinger of potential disaster and chaos. Droughts, floods, or pollution through such human-created events as oil spills, and all manner of ecological catastrophes are poised to upset the delicate balance of every natural element, including the rhythms and the sustaining foundations of animal and human life on this fragile planet that we inhabit.

The work by Soledad Salamé that I have the privilege of seeing every day, exudes an air of chilliness (naturally) but also one of melancholy. Yet the sense of dislocation that I experience when contemplating this print is hardly the same as when I look at a more conventional work by nineteenth century Romantic era artists who traveled to far-away places in order to experience the awe and grandeur of nature. Soledad’s “inner portraits” of natural environment are not simply renditions of a time or place but acute investigations into the inexpressible qualities that inform the world around us and can only be intuited, not observed. A product of the artist’s expedition to Antarctica with naturalist fellow-travelers, the “Aguas Vivas” series was one of multiple testimonies to a constant theme in her work – intimate engagement with an ever-mutable nature. Salamé’s investigations into the natural world have become more poignant and more urgent, even during the almost-twenty-year span between her initial incursions into the world’s southern-most continent. As climate disasters and subsequent human catastrophes continue to mount, Soledad Salamé has made it her principal concern to document, interpret, suggest, evoke and counsel her viewers as to the imminent risks to the all the earth’s inhabitants, especially the most vulnerable. These include the migrant populations with which she deals in her most recent exhibition, people who must flee their habitats for such impending natural calamities as lack of sufficient water, or human-precipitated cataclysms as violence of all descriptions: political, moral, substance-induced, or simply the inexplicable hatred that can be conceived on the part of one group for another.

As a historian of the arts of the Americas, I have long been drawn to Salamé’s art, (since I was first introduced to it in the early 1990s) for the kinship that it demonstrates with visual, moral and literary concerns that have been pervasive in American culture (south and north) since the late eighteenth century. When Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt made his epic trip to South America and the Caribbean from 1799 to 1804, his recordings and intense involvement with the natural life of the flora and fauna of the Americas, codified for European audiences, the thousands of years of importance that nature and its constant mutations had had for indigenous peoples throughout the Western Hemisphere. In the literature produced during the American Enlightenment and into the later decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the vast pampas of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, the volcanoes of Ecuador and Mexico, the Atlantic and Pacific shorelines and the power of ocean water for transport and river water for substance, all played determining roles in the artistic imagination of the Indigenous, Spanish, Portuguese, English and French-speaking populations, whether tribal descendants or colonists from Europe.

Soledad Salamé is one of the most distinguished artists of our time for harnessing the essential and most urgent messages provided to us by the natural world. With near-shamanic prescience she has understood the warning signals offered by the cataclysmic droughts, raging forest fires, ever-increasing extinction of animal species and many more cautionary chapters in the recent annals of nature. She employs these in order to create images that serve as paradigmatic semaphores for imminent danger. However, I do not wish to suggest that the art of Soledad Salamé consists principally of only topical themes or deals simply with issues of impending disaster. I think of her as a contemporary heir to the concerns expressed by nineteenth century artists from all corners of the Hemisphere who have turned to nature in the spirit of both celebration and caution. U.S. artist Frederic Edwin Church and Uruguayan painter Pedro Blanes Viale understood, in their extraordinary images of waterfalls, that cascading water was more than a picturesque feature of the wilderness. Water’s power may be harnessed for energy – until it runs dry. Mexican artists José María Velasco (as important as a naturalist than as a painter) or the twentieth century volcanologist-artist Gerardo Murillo (popularly known by his assumed Nahuatl name Dr. Atl [meaning “water”] employed representations of volcanoes as metaphors of both grandeur (national and spiritual) and potential destruction (see, for example, Dr. Atl’s many depictions of the eruption of Paricutin that unexpectedly and violently surged in a cornfield in the State of Michoacán in 1943). I would also undoubtedly connect Soledad Salamé with some of the most extraordinary women artists of natural subject matter in the twentieth century. Georgia O’Keeffe is most remembered for her desert landscapes of the U.S. Southwest. While these are impressive modernist icons of visual experimentation they are, at the same time, warnings to her audience of the fragile balance between nature and the incursions of humankind into the desert climes of New Mexico. Similarly, Emily Carr, whose career developed in the Province of British Columbia, Canada, was an assiduous reader of the biological timeclock of the forests and wetlands of Vancouver Island. These and many others form the art historical genealogical chart form which Soledad Salamé descends. Like Velasco, Carr or O’Keeffe, she calls attention to natural realities. Although her means and forms of expression are thoroughly contemporary, with all of the experimental forms and materials that she has employed, Salamé nonetheless forms the most recent link in a long and powerful chain of artists and writers for whom nature and its supremacy over humanity – and its unstable delicacy – stands as the quintessential subject for reflection, meditation and as an implement in a “call to consciousness,” an admonition for all to heed: Nature can protect, but it can also destroy – and be destroyed.

Edward J. Sullivan is the Helen Gould Shepard Professor in the History of Art at New York University. He specializes in the arts of the Americas in the modern and contemporary eras. He is the author of more than thirty books and exhibition catalogues and has curated exhibitions of Latin American art in various museums throughout the world.

Download PDF Here

Fig. 1. Detail of Antarctic Reflection I; Print Drawing , Graphite and Acrylic on Mylar.

Fig. 2. Antarctic Reflection, installation at the Museum of Fine Arts Chile, 2006

Soledad Salamé: Considering Boundaries

by Clayton Kirking

Transart, Houston, 2021

In May of 2001 I wrote for Soledad Salamé’s exhibition En el Laberinto de la Soledad a very large installation that was mounted at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago, Chile. The show opened on September 12, 2001. The world changed before the opening. Now I write again for Forced by Nature, which will open on September 9, 2021, once again in a world that has changed.

Since the events of September 11, 2001, this country has suffered a nearly catastrophic financial collapse, a presidential administration that evidently intended to mutate the fundamental DNA of democracy, and now a viral pandemic that has rebooted the globe. The relevance of Salamé’s work has not only survived these calamities but transcended them and grown more pertinent.

Throughout her career, perhaps throughout her life, Soledad has viewed the world as being in a state of crisis both politically and environmentally. Her work has sought to pinpoint issues of extreme tension and illustrate them in a manner that emphasizes their vital nature and leads the viewer to a deeper understanding of causes and effects. At age eighteen the artist left Chile and immigrated to Venezuela and her global outlook expanded further, a process that has never stopped. In her installation entitled The Labyrinth of Solitude she laid bare both the fragility and extreme beauty of our global environment. Since 2001 she has witnessed the ravages of increasingly bellicose politics and progressively deteriorated environmental conditions that have forced the flight and migration of millions of people internationally. Then, as 2020 dawned, the world rapidly slid into a pandemic that has left millions dead and yet remains of unknown proportions.

The objects presented in Forced by Nature represent some of Salamé’s most refined work. This refinement is expressed not only in the artistic vocabulary that the artist has developed over the course of her career, but in the variety and use of media. Her extreme facility allows her to express herself in diverse techniques using skills that she has honed in her studio, focused through her travels, and cultured with extensive reading and research. She is able to understand relationships that exist among enormously complex subjects, climate change, immigration and racism, but conceive images that exemplify the more quotidian aspects of life such as agriculture, family stability, craft, social justice and the fragility of interpersonal networks. Some of the work was created before the COVID19 pandemic, other pieces while the virus tore through countries, cities, villages and homes. In any case, what Salamé demonstrates here is an astonishing aptitude of tools, skills and media.

The glass newspaper installations are neither print, nor sculpture but make a profound, eloquent point of the lack of transparency within our culture; embroidered frontpages draw a direct connection between the daily lives and pursuits of migrants and the ponderous weight of the prevailing body politic; sandblasted blown glass works elegantly imply both the depth of our humanity and its fragility. Two new fabric works, both made during the current pandemic, have emerged from that experience. Air, three large screen-printed and hand dyed panels of silk, invites viewers to examine it at close range, to appreciate the color and movement and realize that the menace of COIVID is invisible, in the air, everywhere. For Our Heroes solidifies that fear, picturing washed surgical masks drying in an open window. These can be seen as the culmination of Soledad’s years of consideration, which have resulted in this exhibition: life is fragile, it flows and changes, and is often made manageable by simple, daily heroic acts—washing a mask for a nurse to wear the next day.

Postscript

A work that I believe eloquently captures the essence of Salamé’s intellect is not in the exhibition. It was not made by the artist but collected by her on the Mexico/Texas border. It is an embroidered felt and fabric sleeve that slips over a bottle or glass to keep the drink cool. NO WALL is stitched in bright yellow felt. A border wall does so much more than slowing immigration, it destroys economies, families and lives. Soledad Salamé quickly grasped the fact that this simple handmade tool embodied the politics, lack of transparency, corruption and denial that shape our world and may determine its fate.

Clayton C. Kirking is an independent curator and information manager. In 1992, Kirking became the first Curator of Latin American Art at the Phoenix Art Museum, which established the department that same year. From 2001 to 2015 he served as Chief of the Art & Architecture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Download PDF Here

Photographs by Michael Koryta

The exhibition opened for visitors by appointment only, from Wednesday through Saturday through March 27, 2022.